My uncle Jimmy, James Martin Willhite Jr., wrote a book in 1995 describing the first few years of the family’s life on the Tensas River at Flower’s Landing. His book, My Family and the Tensas , included on this site, gives a first hand account through the eyes of an eight year old, of how Jim taught them to survive and use the resources of the wilderness to make a living for themselves. It serves as a valuable resource to me in writing about those years.

The house he bought at Flowers Landing was nothing more than a barn, but served as shelter for Jim and the older boys over the next year and a half as they prepared for moving the family. They spent day after day hunting, trapping, and fishing on Tensas River, cleaning the fish and game and stretching the hides, clearing land, and working on the house to make it more livable. Jim was traveling back and forth from Tensas to West Monroe, bringing the fish, meat and furs to the markets in the Monroe area, or selling them at Newellton.

He would then buy supplies for the boys such as food, clothing, ammo, and building materials for fixing up the house. He also took Nita back and forth with him, hoping to help her recover. It was during this time that she met and married my uncle Johnny White, in May of 1933, and they began to farm nearby on Newell Ridge Rd.

Prohibition had ended, and there was no longer a market for his homemade whiskey., so Jim spent his time trying to make as much money as he could to get them out of debt. Etta Mae stayed on White’s Ferry Rd. with Carrie 10, John A. 9, Jimmy 8, George (Tut) 3, and Charles (Bubba) 1. She worried about the older boys when Jim left them alone at Tensas, praying daily for their safety, and when Jim was with them, she dealt with the care and feeding of the smaller children alone, now without Nita’s help.

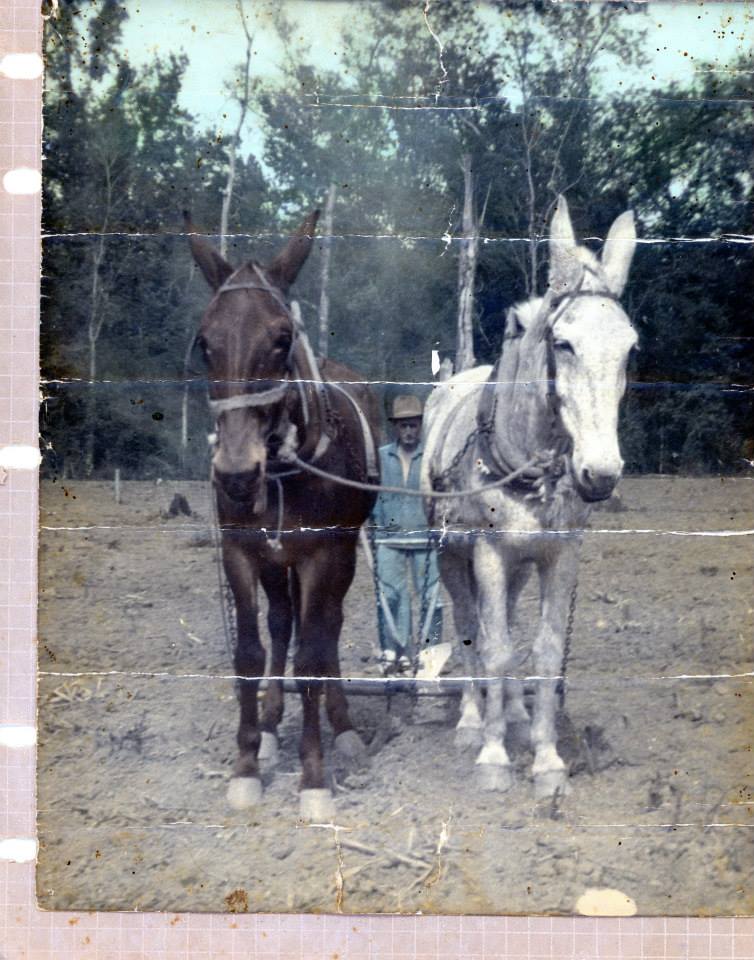

Charley White, Nita’s brother in law, plowing with mules

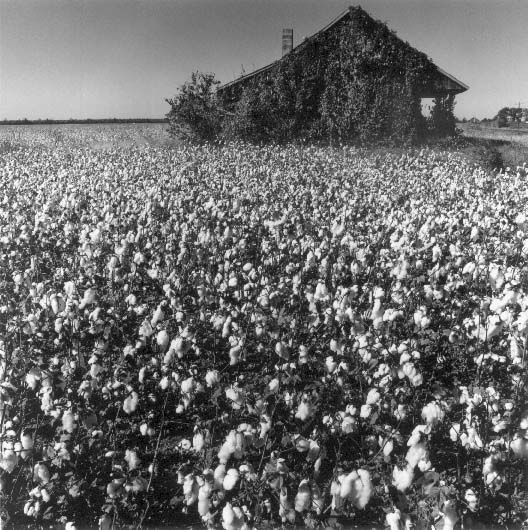

cotton field like those on Newell Ridge Rd.

Johnny White

Nita, Carrie, Emma Lou, and Jan in the 1940s

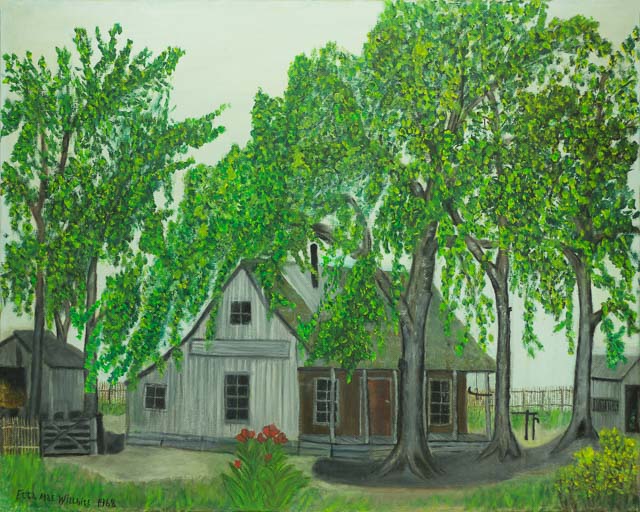

Finally, in January 1935, the family was reunited when they moved the last of their household belongings to the house at Flowers Landing on the banks of the Tensas River. They moved in a 1930 flatbed truck, but when they got past Somerset, the road was so bad that they had to hitch mules to the truck to pull them and their belongings on to the house. According to Jimmy’s book, the repairs to the house were not all complete by January 1935, even though the family had already moved in. His description of waking up on his first day there in the freezing cold with snow in his hair is followed by a description of the house. “I had visualized a fancy two story home like the ones you see on big ranches and plantations. Well, it was a two story alright. It had two rooms upstairs. It was built with mill run oak and sweet gum lumber and there were no battens over the cracks on the walls. The roof was made of rough oak boards that had warped and curled up on the sides to a point that you could see the sky through the cracks.”

It was indeed a primitive place, compared to any of their houses in West Monroe, which were near paved streets and had electricity, some running water and possibly indoor plumbing. The surrounding property was barely cleared, the yard consisted of weeds and dirt or mud depending on the weather, and the road leading to it from Somerset or Newellton was no more than a muddy trail through the woods after the gravel road ended at Newell Ridge. Glen remembers it this way, “ The road was what is now Newell Ridge and kept going and went through where the Humphries lived curved around to Mother and Daddy’s house. In order to get a road up and down the river, the land owners had to clear the right of way. It would be so bad during the winter and spring that it would take four mules to pull a wagon. After the landowners cleared right of way, the parish would come in and put a little gravel down. The ice truck would come from Newellton and the grocery bus would come when they could get down it.”

In 1938, after Carl, Jim’s younger brother, bought property and moved to a place a little further up the river, he and Jim cleared the road to their properties and petitioned the Tensas Parish Police Jury to declare it a public road so that it could be maintained by the Parish. Their petition was granted and the road was graveled with the condition that Jim and Carl would be responsible for keeping trees and debris cleared from the right of way. (Tensas Gazette)

With the family all together, even in harsh conditions, they were better off than some at that time, and they wasted no time on self-pity. In Chapter 7 of his book, Jimmy tells about the work they did. “When we are growing up during the depression everyone who was old enough worked. When I was eight years old, I was expected to be out there working alongside my older brothers. I may not get as much done as they did but I worked just as hard. While some of us were working with the crops, clearing land and or doing anything else that needed doing, Dad and two or three of the older boys were always fishing, trapping, frog hunting, alligator hunting, or doing anything they could to keep some money coming in.” O.D. left home by the summer of 1935, and the older boys, Derwood and Oliver and John. A did enter school at Newelton, along with Carrie Mae, but none of them attended enough to graduate except Carrie Mae.

Although most of the woods surrounding their property up and down the river was considered a refuge, with no hunting and trapping allowed, it served as the sole source of income and food for the family during that first year, and in later years as well. Not all land along the Tensas was part of the refuge, and game from the refuge roamed back and forth freely on it. The lines were sometimes blurry, and trapping and hunting during the day in season was legal in some places. Jim was stopped by a game warden once in 1925 while trapping, but not arrested. Jimmy mentions this in his book, as well as how skilled they would become at avoiding arrest when they were hunting deer for food at night. In the chapter “We Became Experts“, he tells of a close call when he and John A. and Derwood were bringing the deer out in the dark, and they were able to paddle their boat within feet of the game wardens without being detected.

The papers of that day are full of trespass notices, arrests, and articles touting the crackdown on poaching, a widespread problem due to the severe economic hardships of the time, and the draw of the Big Woods as a place where the game was premium and plentiful. There were two kinds of poachers. The ones who came to kill for the joy of killing were rich hunters and politicians from other parishes or states, looking for trophies or bragging rights. Reports of arrests by game wardens for two hunters killing six or more deer, or finding hundreds of squirrels killed and left hanging in the trees to rot, proved they were not hunting for food. (The Tensas Gazette)

hunting camp Tensas woods

cypress break Tensas woods

The other kind, like Jim and his boys, were hunting to survive. They, like other families all over Louisiana, respected the woods and viewed the game as a provision for their families, not to be abused. In the first chapter of Jimmie’s book, My Family and the Tensas, he quotes Jim’s lesson on this when they had killed three hogs and Derwood wanted to shoot more. “Afterward Dad explained we had three hogs on the ground and didn’t need any more meat. Then he said never kill any more game than you need to eat. If everyone did this there would always be game to hunt. Dad field dressed the three hogs and headed home.” The game wardens respected that, since they were local men who had been raised doing the same thing. They knew about the hunting and did make attempts to catch them in the act, but did not try hard enough to actually arrest them with the game when they got away.

The task of feeding and caring for a family of twelve in primitive conditions would be daunting for anyone, but Etta Mae embraced it with fierce determination and a song on her lips. She was very interested in cooking and good nutrition, and had been a member of the Home Demonstration Club since the 1920s as stated in this article when she was honored for 50 years of membership. There were numerous other families living in the area at the time, and Etta Mae became a leader among the women, sharing ideas about cooking, canning, child care and nutrition.

According to stories Glen was told. ” Nita left first, then O.D. and that left 6 or 7 kids at home. Derwood said he never got full until he was 18 years old! She had a wood stove and a big ole pan, and she would cook biscuits about the size of a softball. She would shut it off at 40…….refused to cook more than 40 biscuits in the morning. Every single day…..what happened was one of the boys…..took turns….would get up and get the fire started in the cook stove. She knew every song in the songbook….the Baptist Hymnal. We’d be up in the loft bedrooms and she would be singing in the kitchen. Sometimes playing the piano. She was 13 years old when she started playing the piano in the church where she grew up. She became a pioneer woman when they got married. And she was pregnant a lot of the time. Grandpa played the violin. They used to have a little band with Uncle Carl, and they’d get together on Saturday afternoon and play. Mother played the piano and Daddy played the violin.“

Besides biscuits, there was also venison, pork, and eggs along with fresh milk from the cows. She cooked enough at breakfast to pack lunches if Jim and the boys were going hunting or fishing for the day, or camping out at night, then cooked another meal for them all for supper. Cleaning up the kitchen was a major chore in itself. Water had to be hand pumped outside and brought in for washing dishes, then heated on the wood stove, creating comfort in the winter, but almost unbearable heat in the summer. Of course, dishes, cooking utensils, and pots and pans were all washed and dried by hand after breakfast, then again after supper.

After the kitchen chores were done, more work awaited the girls and younger children at home. By the summer of 1935, Etta Mae was pregnant with their eleventh child, Emma Lou, with Bubba still in diapers, and four year old Tut to watch after. Nita had left home when she married two years before, and Carrie, at eleven years old, John A. 10, and Jimmy at 8, helped watch the babies and did other chores such as bringing in the wash, gathering eggs, feeding the chickens, and milking the cows, when they weren’t at school. That left Etta Mae, even though she was pregnant, to do the heavy cleaning like scrubbing the floors, washing, mending, and ironing clothes, growing the garden, picking vegetables and canning.

Glen remembers one wash day like this, “I remember once when I was five years old, four or five families would get together once a week to wash clothes at our house. They would build a fire under a big cast iron pot outside in the yard and have a couple more pots for rinse water. In the house they would heat starch in a dishpan on the stove. The families lived across the river on the Head place…..two different Matthews families lived in houses over there. One day the women were washing and took a dishpan of hot starch off the stove and set it down on the ground. A toddler backed up and sat down in the pan of hot starch…… Mr. Ed Sikes, son Roy Sikes sat down in the starch. Old people had remedies for everything…..they took butter and coated him with it…….temporarily. All his back was scarred after that.” Etta Mae worked hard at holding the family together during those difficult times, taking care of their needs and praying for each of them every day, but she could not stop the changes that were sure to come.

For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.

Jerimiah 29:11

Recent Comments