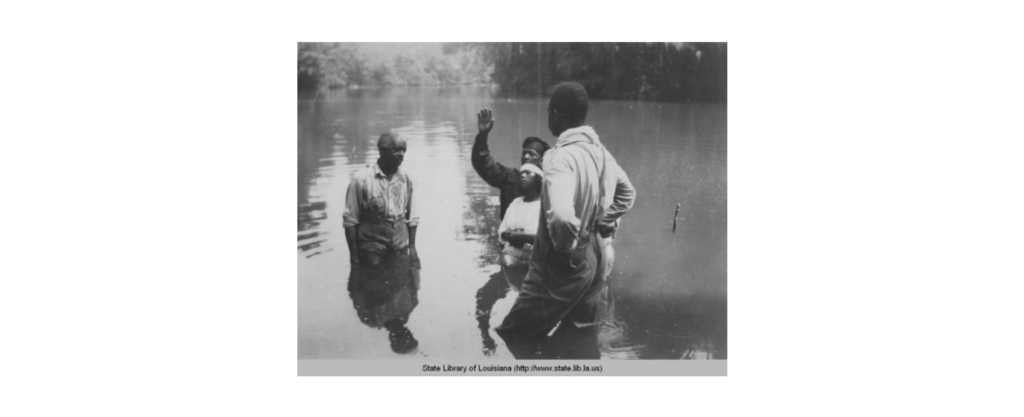

As the service draws to a close and our pastor ends the final prayer, we move out of the sanctuary with a thousand other people, greeting those we know with hugs and handshakes, and those we don’t know with smiles and hellos. Although our congregation is predominately white, we also have families of Asian, African, Arab, and Hispanic descent attending our church. Such was not the case for us growing up in Tensas Parish.

The churches were separated by race, a choice that is much the same today, along with other aspects of life that were not by choice. There were separate public waiting rooms at the hospitals and bus stations, separate water fountains and restrooms, no access to cafes for blacks, and separate rooms at bars. Blacks had limited access to other public facilities like the movie theater and the library, all which felt normal to us at the time, since our parents and our leaders taught us to believe “separate but equal” was the right way, a concept that seems ridiculous to us today, and was rejected by the Supreme Court in 1954, in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. (Wikipedia, Timeline of the Civil Rights Movement) Blacks were not treated as equals to whites, and I wince as I read some newspaper articles up through the 1960s where the names of black people were always followed by, “a Negro”, or courtesy titles such as Mr. or Mrs. were omitted, even for professionals such as teachers. (The Tensas Gazette July 31, 1964)

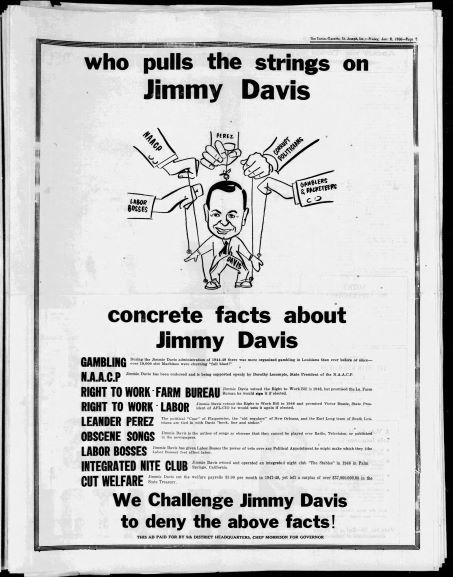

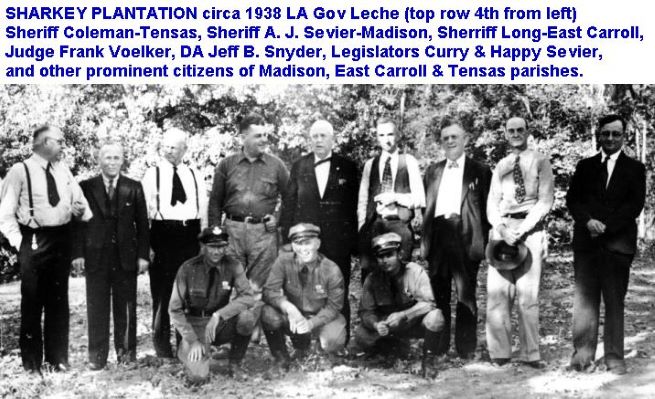

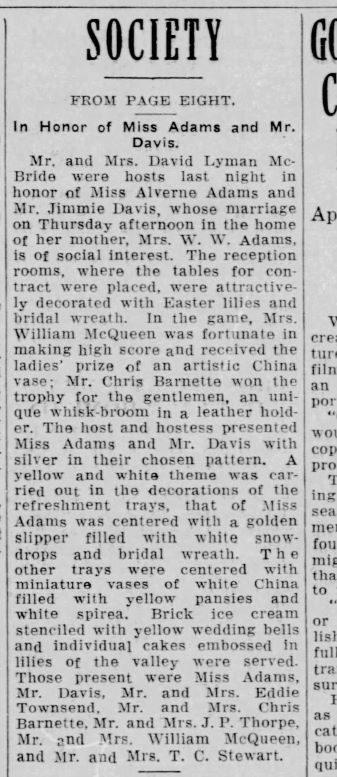

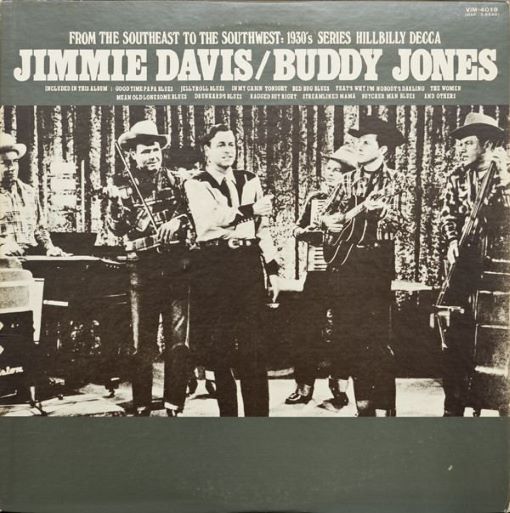

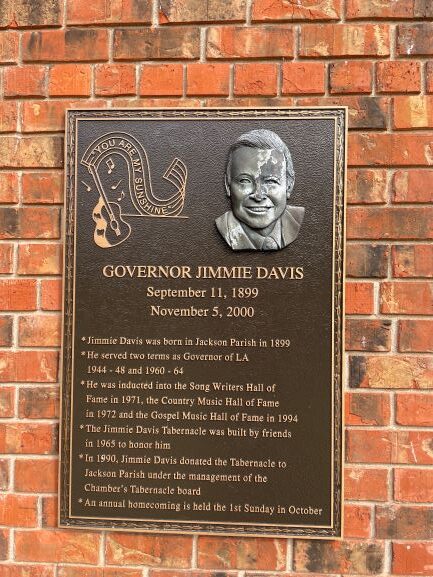

Although Jimmie Davis spoke of bringing the people of Louisiana together, and did much to improve the health care system, infrastructure, and programs for the underprivileged, he was no different from most Southern politicians of his day in standing against the rising tide of civil rights, a requirement at the time if you wanted to get elected. Davis proclaimed he was “1,000 percent” for segregation and promised “no retreat and no compromise” on the issue, however, he did not fuel the fire with hate filled statements as others holding high offices in the South were prone to do. He vowed to make facilities truly equal for blacks and whites and went so far as to comment, “Right-thinking white people and right-thinking colored people know segregation is the best and only way of life in the South.“ Davis’ opponents were relentless with negative ads about him which he refused to respond to, but further stated, “If there ever was a time when our state needs peace and harmony, it is now,” maintaining this theme throughout his campaign. (64 Parishes)

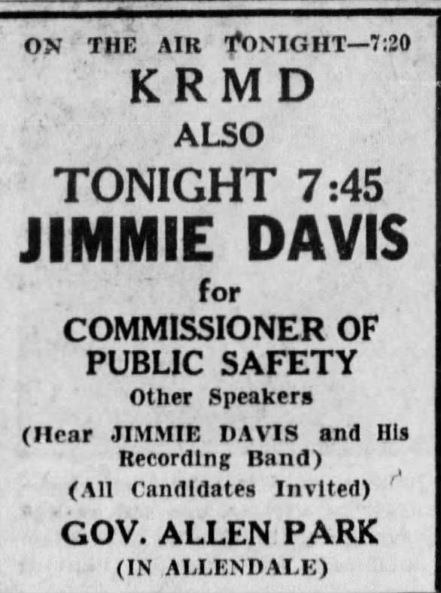

Negative ad against Jimmie Davis

Positive ad promising support for all schools and teachers

One article written by a black newspaper editor, Davis Lee, was widely circulated and reprinted in The Tensas Gazette, and outlined that same sentiment from the black point of view. In it Mr. Lee called some of the protesters “agitators and pressure groups that do not consider the cost of forced integration on the black people.” He cites examples of more black teachers employed at higher pay in the South than in the North and East, and predicts that 75% of them will lose their jobs if integration of the schools is enforced. Lee claims to have traveled extensively throughout the South and interviewed thousands of blacks ranging from poor sharecroppers in Mississippi to wealthy business owners in Atlanta, none of which want integration. He states that they want their own schools with equal facilities and pay, and to be treated with equal respect. Mr. Lee goes on to say that blacks in the South are in a better spot educationally, politically, and economically than elsewhere in the country, that race relations are improving, and that blacks and whites working together can do more than the courts, legislation, or pressure groups ever can, and that forced integration would set black progress back 50 years. (Davis Lee, Newark, New Jersery Telegram 1954)

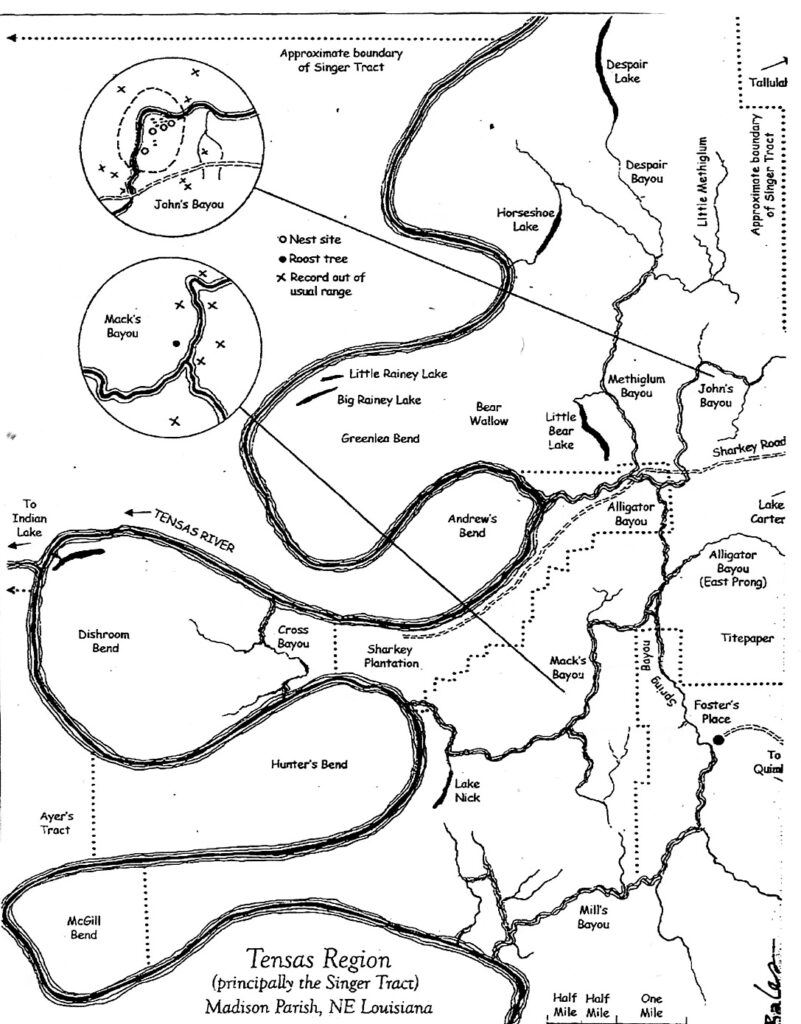

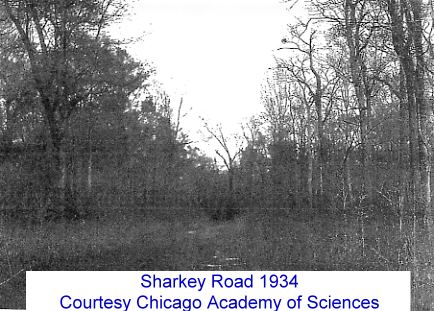

Tensas Parish schools were segregated and each town in the parish was loyal and protective of its own schools. In response to state funding mandates in 1965, a parish wide plan was formulated to consolidate the white schools. The plan joined Waterproof High School and Davidson High School into one, leaving Newellton High School, and building new elementary facilities in each town, but the plan was rejected when brought before the voters. (The Tensas Gazette Oct. 22 1965) Yet, black students were already being served in a consolidated high school, Tensas Rosenwald High School, in St. Joseph, and bused from Newellton and Waterproof, requiring some students to board the bus at 5 a.m., and return home after 5 p.m. Rosenwald had an attached elementary school that served black students in the St. Joseph area. Lisbon Elementary in Waterproof, and Routhwood Elementary in Newellton served the black elementary students in each of these town. (The Tensas Gazette) Like each of the white high schools, Rosenwald H.S. prided itself on academic and athletic achievement, with qualified teachers and coaches, and strong community support. (The Tensasan 1965, Rosenwald High School Yearbook) Everyone loved their schools, and there was reluctance to change, on both sides of the aisle, but to paraphrase Bob Dylan, “times they were a changing.”It was evident that the peace and harmony that Governor Davis and others wanted could not be achieved through the “separate but equal” policies any longer.

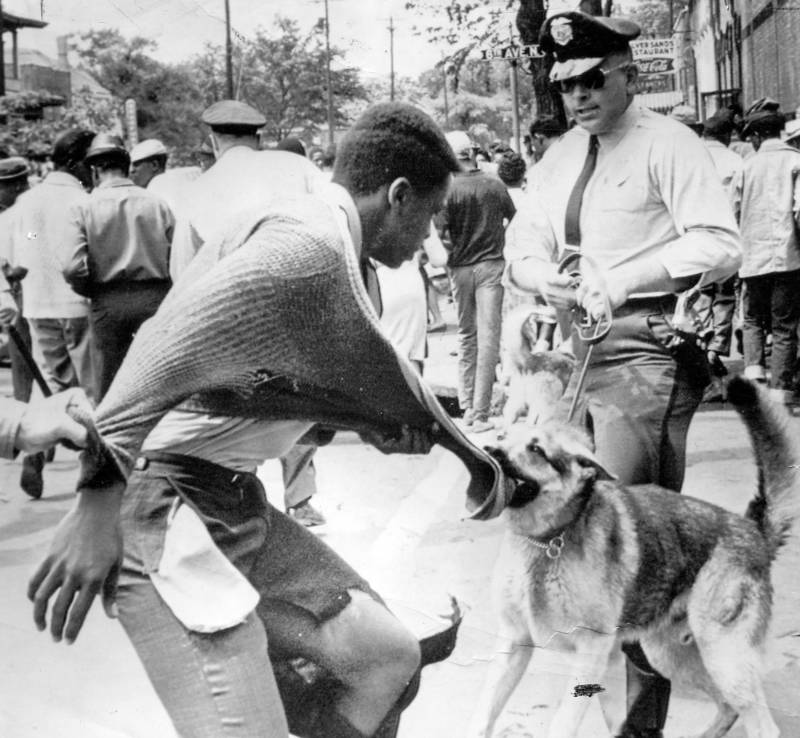

In our unworldly existence, we understood little of the real reasons for the civil unrest that Walter Cronkite reported on the evening news, since our experience with the blacks in our community was limited, but in sharp contrast with the scenes we saw playing out in cities across the country on TV.

Selma Alabama 1965

Dog attacks protester Birmingham 1963

KKK support for Goldwater Republican National Convention 1964 San Francisco

Dr. Martin Luther King addressing the crowd at the March on Washington, August 1963

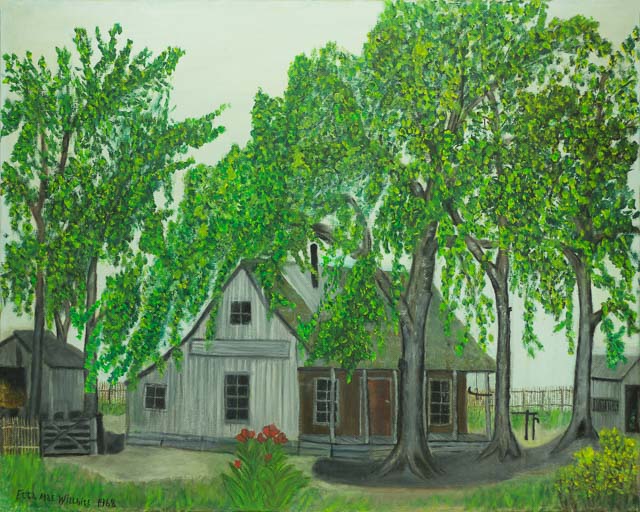

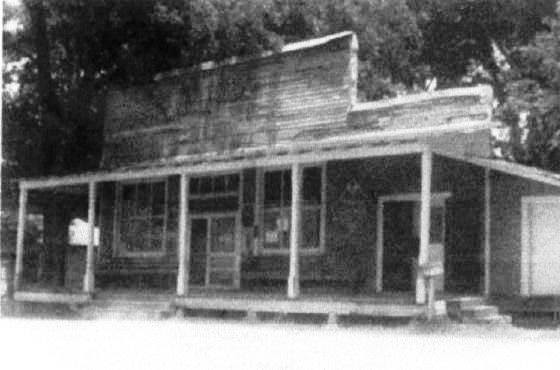

It was a mile and a half from our house to the store on the corner of Newell Ridge Road. As children in the sixties, my brother and I would ride our bikes there, sometimes balancing one of our younger sisters on the handlebars or the back fender seat, a much easier task after our road was paved. A rough wooden building with a rusty tin roof and tar paper siding that was patterned to look like brick, the old store was randomly adorned with a wide variety of metal enameled signs advertising everything from Sunbeam bread, to Lucky Strike cigarettes. The single gas pump that stood in front had a hint of red paint showing through the rust and a clear glass gas tank on top that was filled by a hand pump from underground. Once filled, you could then remove the hose and let gas flow into your vehicle or can. The store was owned and run by an elderly African-American couple whom we knew as Son and Coreen.

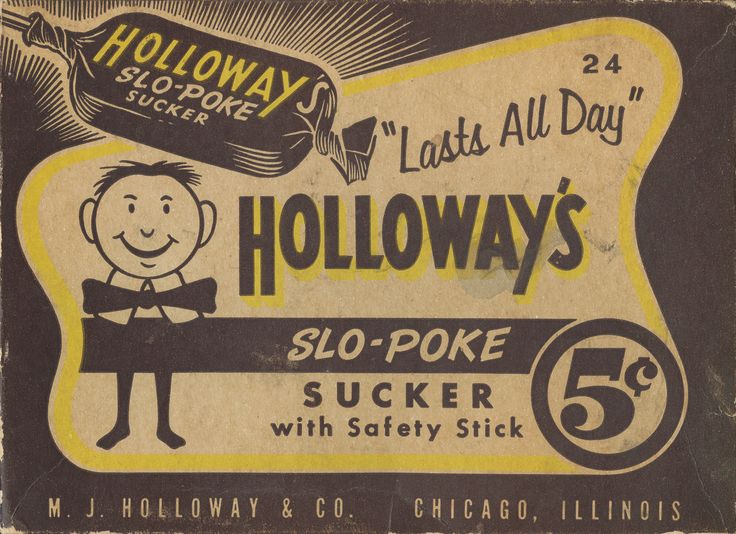

They were kind and patient with us as we surveyed the displays of penny candy that included Mary Janes, candy cigarettes, and large banana LaffyTaffys, or tried to choose between a Slo-Poke sucker, a Stage Plank cookie with its scalloped edge and pink icing, or a Moon Pie. If we had enough money for a Coke, they would help us use the slider Coke machine, showing us how to slide the bottles down through the icy water to the place where they could be removed, flashing gold teeth when they smiled and calling us “baby”. The RC Colas and Nehi orange sodas were in another cooler nearby that had a glass door, and could be opened by us. There was always a large jar of pickled pigs feet or pickled eggs on the counter, and I remember their dark wrinkled hands with pink palms taking our coins from the well-worn wooden counter where a single bulb hung for lighting. We’d sit on the front step near the screen door and enjoy our drinks, savoring the cool sweetness in the oppressive heat and humidity. Then we’d return the bottles for another piece or two of penny candy before pedaling back home on the newly paved road, shiny black, with half melted asphalt in the hot sun.

Soda cap for returnable bottle

Penny Cancy

Slo Poke Ad

Stage Plank iced cookies

Pickled pigs feet and pickled eggs

Candy cigarettes

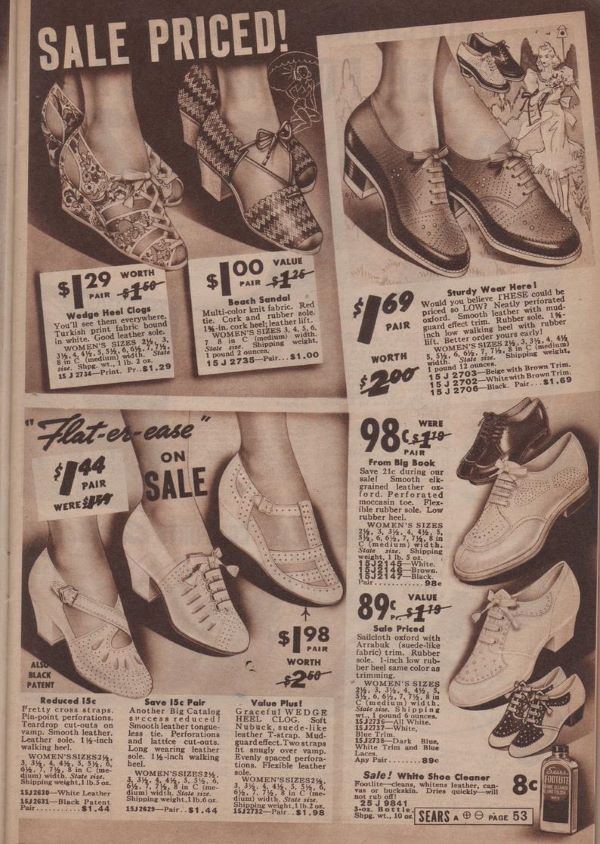

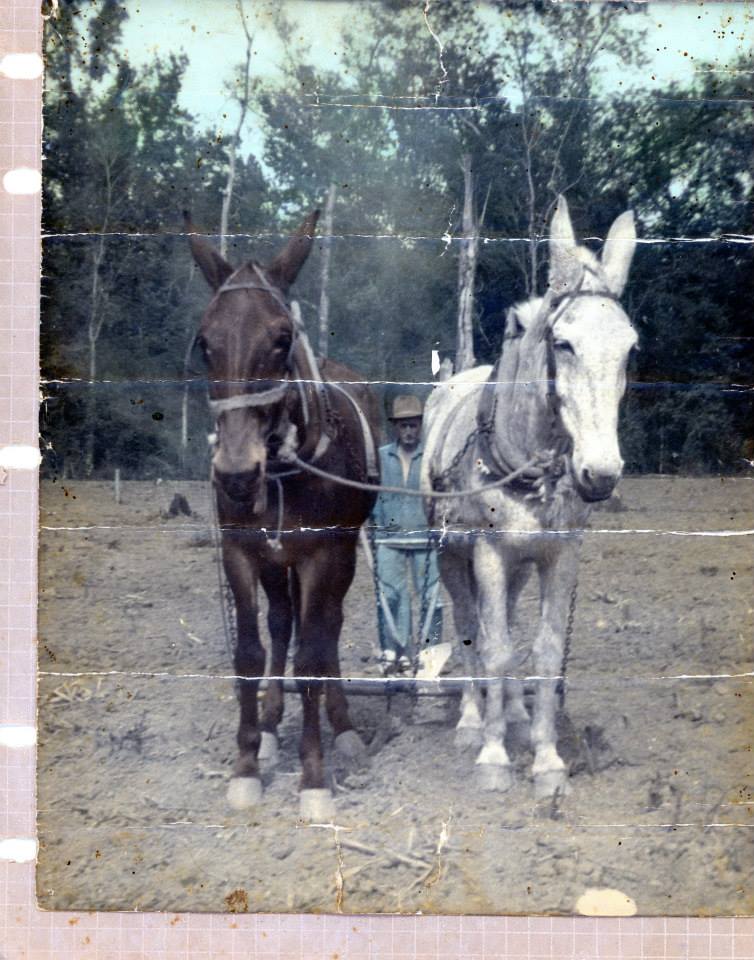

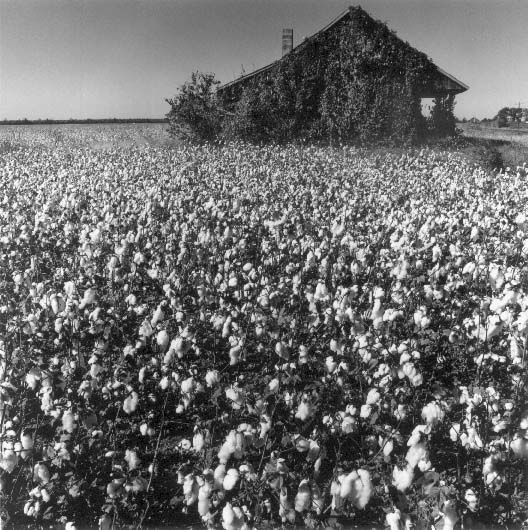

We did all our own work, the cleaning, the laundry, the farming, and the mowing, and unlike the whites depicted in popular movies of today like The Help, we were in no position to wield power over anyone. Daddy would hire field hands for a few days at a time when the Johnson grass and cockle burs in our fields were more than we could handle. When he did hire workers in the fields, we were all out there working alongside them, pausing for breaks when they did, making sure they had plenty of water and anything else they needed. By the time I was twelve years old, the task of taking their lunch orders, and then driving the five miles to the store at Somerset to get them, fell to me. Somerset store sold fresh lunch meat, and I would fill their orders for summer sausage, salami, or bologna, RC Colas and Moon Pies, and pay with the money my daddy gave me. Our lunch break would then begin when I returned, eating meatloaf sandwiches and cream filled cookies, with Koolaid, on the porch while the workers sat nearby in the shade.

Some black families that lived on Newell Ridge road at the time had been there for years, their ancestors originally receiving land from plantation owners after the Civil War. They farmed their own small acreage or hired out to help other farmers like us with their crops. Others worked full time in town or had other enterprises, one of which I was surprised to learn, included a popular brothel visited by men of both races from across the parish. The older folks had known my daddy’s family since he was a small child, and they called him “Mister Little Brother” and my mama “Miss Little Brother”, as was the custom at the time. They included Son and Coreen Claiborne, Riley and Pearl Robinson, Lee and Sarah Robinson, Calvin and Louise Holman, the Bert Piazzas, the Webb Jacksons, Willie Brooks, Thelma Williams, and others. I was impressed with Thelma Williams, a teacher, since she lived in what was probably the first brick house in the Newell Ridge and Flowers Landing area, and vowed that I would be a teacher some day, partly because of her.

Nationally of course, and as close as Jackson, Mississippi, racial tensions continued. The riots were fueled by police brutality, hate crimes of the Klan, and unfair political maneuvers by white politicians. These actions were designed to bypass federal laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that outlawed racial discrimination and segregation in employment, schools, and public places. (Mississippi Encyclopedia) The following year, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law, outlawing practices designed to keep black citizens from registering to vote, causing more protests when it was not enforced.

In this dark time, our country was involved in the Cold War with the Soviet Union and the real war in Vietnam, and was also dealing with the high profile assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Dr. Martin Luther King, and Robert Kennedy, along with others involved in the Civil Rights Movement.(Encyclopedia.com) Legitimate civil rights demonstrations and anti war protests were sometimes taken over by extremists on both sides, and they got much of the news coverage, as they do today. One of our three television stations was WLBT in Jackson, Mississippi, where news reports of the racial violence, assassinations, riots, anti war protests, and police actions came right into our living room, though our understanding of what it all meant was limited at best, even for our parents, but the turmoil was clear, and frightening.

Anti war protest at Kent State

Civil Rights protest turns to chaos

Police dog attacks a protester in Birmingham in 1964.

National Guard in D.C. after MLK assassination in 1968

In 1968 The Supreme Court ordered states to abolish segregated school systems “root and branch”. Five factors — facilities, staff, faculty, extracurricular activities and transportation — were to be used to gauge a school system’s compliance with the mandate of Brown. (Green v. County School Board of New Kent County) This decision caused fear and anguish in both the black and the white communities of Tensas Parish since we were all comfortable where we were, loyal to our own schools, sports teams, teachers and administrators. More than that, the Tensas Parish School Board was struggling with finances since they had refused to take federal funds to avoid forced integration, a tactic that proved to be futile. (The Tensas Gazette) With state and parish revenues decreasing, their budget was stretched thin with construction projects in progress for various schools. The construction projects, a shortage of teachers, lack of proper space, and lack of enough buses were some the reasons that the School Board gave in its appeal to a federal court order in 1969 to immediately integrate its schools, asking for more time to prepare for integration. The appeal was granted, for one year. (The Tensas Gazette Sept. 4 1969) In February 1970, the board presented its plan for integrating all the schools in the fall, and its plan was accepted by the court.

The stage was set for a total reorganization of the public schools in each town, but not everyone was on board with the plan. By the spring of 1970, the newly organized, Tensas Academy was under construction in St. Joseph and fund-raising efforts, hiring of staff, and meetings of the athletic supporters were well under way. It opened in the fall of 1970, with an enrollment of over 300 white students, with the majority of them from St. Joseph and Waterproof. (The Tensas Gazette April 23 1970) When my parents informed me that my siblings and I would be attending, I cried all summer, begging them to let me finish at Newellton, since I was going into my junior year, didn’t want to leave my friends, or stop being part of the band. Their decision was firm, and starting in September 1970, we attended Tensas Academy, making the twenty five mile commute twice each day.

Fifty years later I realize their decision was one that stemmed from their love for us, and was based on what they truly felt was best at the time, even though it required a great financial sacrifice for them. When I graduated from Tensas Academy in 1972, I had experienced instruction from excellent teachers, expanded my view of the parish beyond my hometown of Newellton, formed friendships that are still intact today, and most important of all, met the love of my life. But I can’t help but think of the possibilities. What would it have been like if it had all happened differently? If the parish schools had been consolidated in 1965? If integration had been embraced by all and worked through as a team?

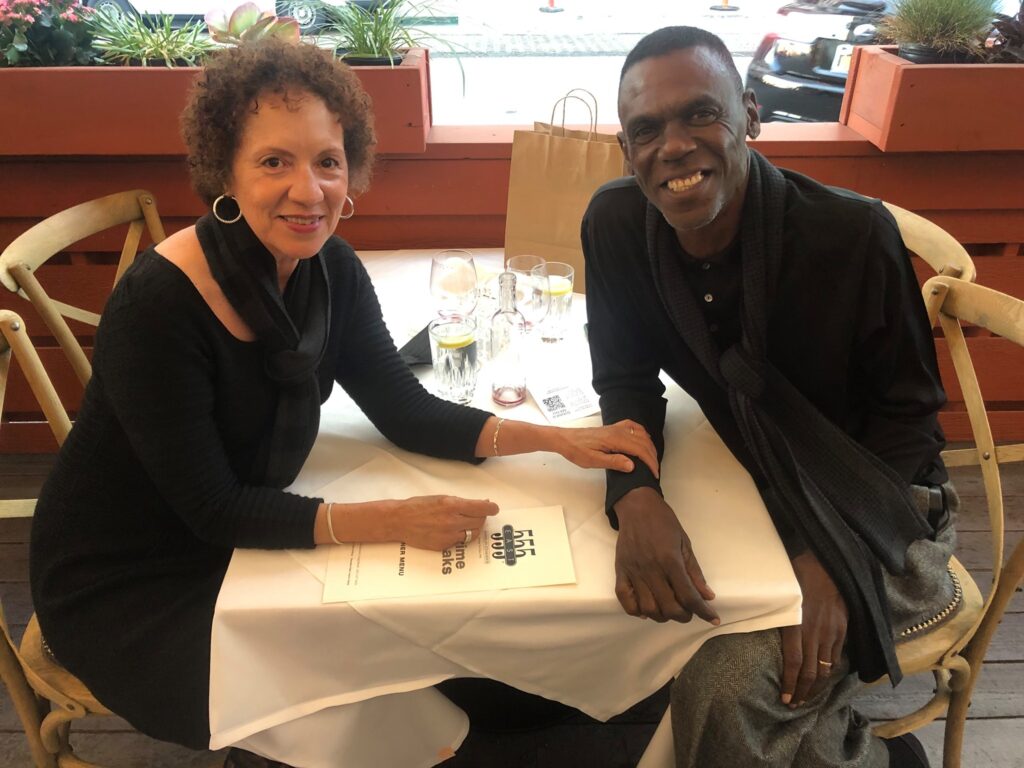

I did not know an African American person my age until I attended Louisiana Tech in the Fall of 1972. Since then, it has been my privilege to know many, from fellow students at Tech, to fellow teachers, coaches, and administrators in my years as a public school teacher, along with the countless students and parents I have worked with and continue to work with today. We have worked together to achieve common goals, laughed together to celebrate our victories, and cried together when life was hard, coming away much richer for it. In doing research for this chapter, I have become friends with someone who has been generous enough to share his experiences with me as a young black person growing up in Tensas Parish in the 1960s, and how he escaped to make a better life for himself.

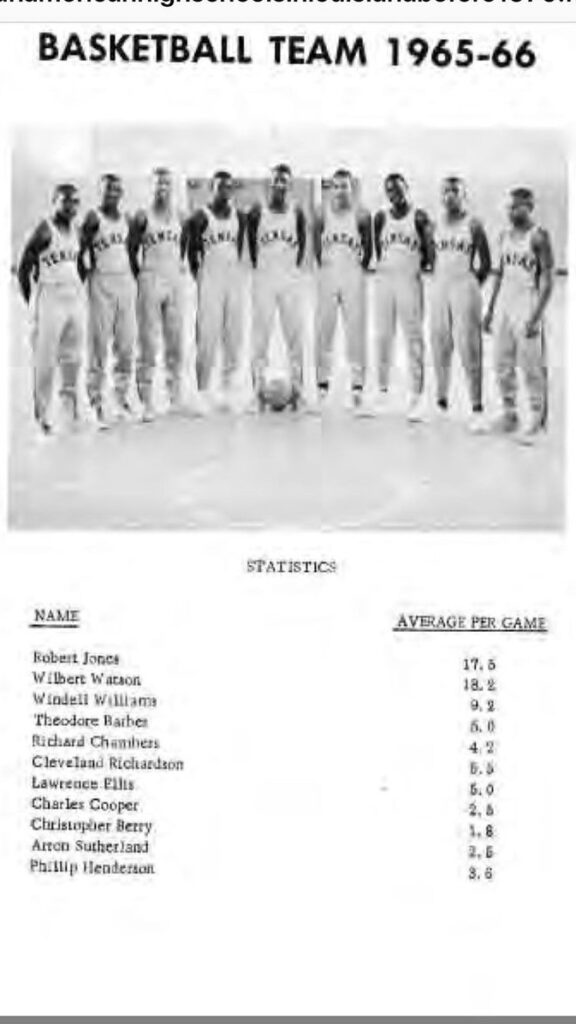

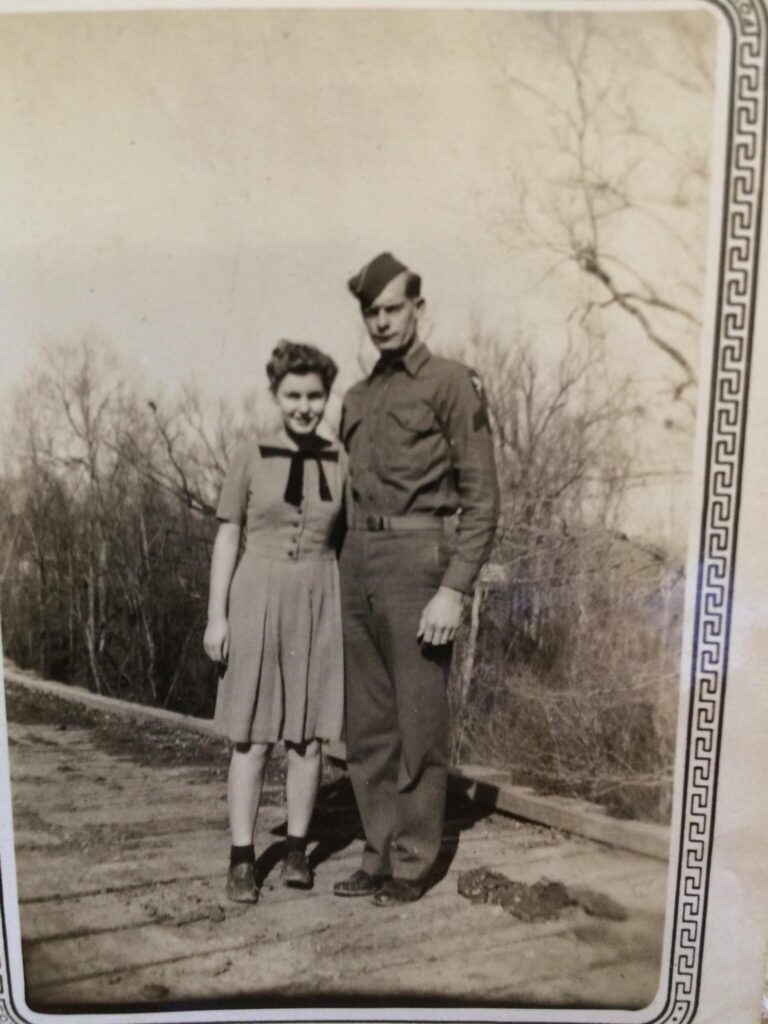

Born in Madison Parish, (Wilbert) Tang Watson’s family moved to St. Joseph when he was young, and he attended Tensas Parish schools until he graduated from Rosenwald High School in 1967. I have included his full interview in a separate page where he tells about his struggles as a dark skinned black kid, often seen in a negative light by blacks and whites alike, but states, “ I never knew any white people either, my age. I do admit I was really curious about white people, and they were not all bad, though, good ones too. Talking about how whites treated black people, some blacks treated blacks just as bad. It was simple most of the time. The blacker you were, the more bad you were treated or not respected. Not all, but some. If your family didn’t have a lot of educated members, others didn’t respect you. Not all, but some. I can say I hated the separate black/white concept and never believed for one minute that whites were superior or better than me. Ha, Ha, Ha, I never believed anybody was better, or could do more than me, given the chance!” This positive attitude, the support of his mother, and the determination and discipline to follow his dreams led him out of Tensas Parish.

When he got his chance to go to L. A., and fulfill his life long dream, he was prepared and never looked back. He met his wife and life long partner, Pamela, shortly after leaving Tensas, and after years of hard work, is comfortably retired in a beautiful ocean side condo in Longbeach, California where he delights in watching his grandson Peyton play basketball at UCLA. Tang came from a large family of seven kids and describes himself and his success this way, “The reason I think I am so lucky and blessed is because I’m a son and the 7th kid, the 7th son. I’m a natural born salesman, I moved to Los Angeles in 1968 and was lucky and smart, all my life. Took the U.S. Post Office test in early ‘68, lucky and smart enough to pass it, even though I didn’t know anything about the Post Office, the 150 questions or anything else city wise. Passed it and began working for them, making almost $3000 a month and I’m 17 years old. It was only me, so I had plenty enough money. No money problems at all. I worked there for about 5 years, taking some classes at the local Junior College. I didn’t like the Post Office kind of work, and knew I wanted to get out when the time was right. I did, and got into sales. Never did anything else but sales to this day. Sold everything from women’s shoes to million dollar houses and properties. Being a natural, made it as easy to sell one thing as another. Sales took me though into some amazing situations, especially commissions sales, which means, if you don’t close your deal, you don’t get paid!”

Tang’s story is a testament to the ideals referred to by Dr. Martin Luther King in his famous I Have a Dream speech in Washington, D.C. in 1963, where he warns against “drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred“, and encourages those who are striving to change to “conduct the struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline.” I mentioned to Tang that I thought race relations were much better now than they were then, despite what we see on TV, and he responded by saying, “You are right, things are way better now than before, and getting better every day in a lot of ways. In almost all ways. We still have work to do, but we all know now that we all can become anything we want. We are a stronger nation when it’s like that.”

Tang and Pamela February 2021

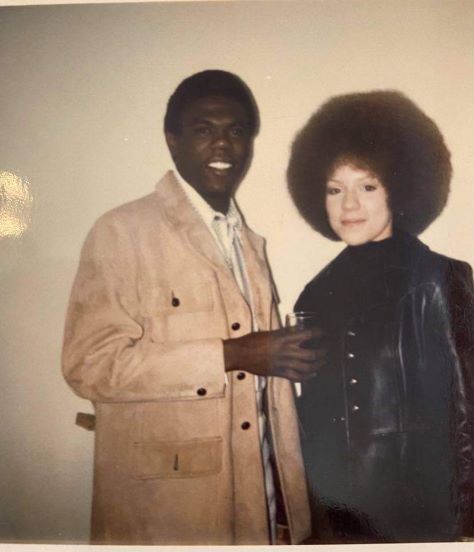

Tang and Pamela in the late 1960s

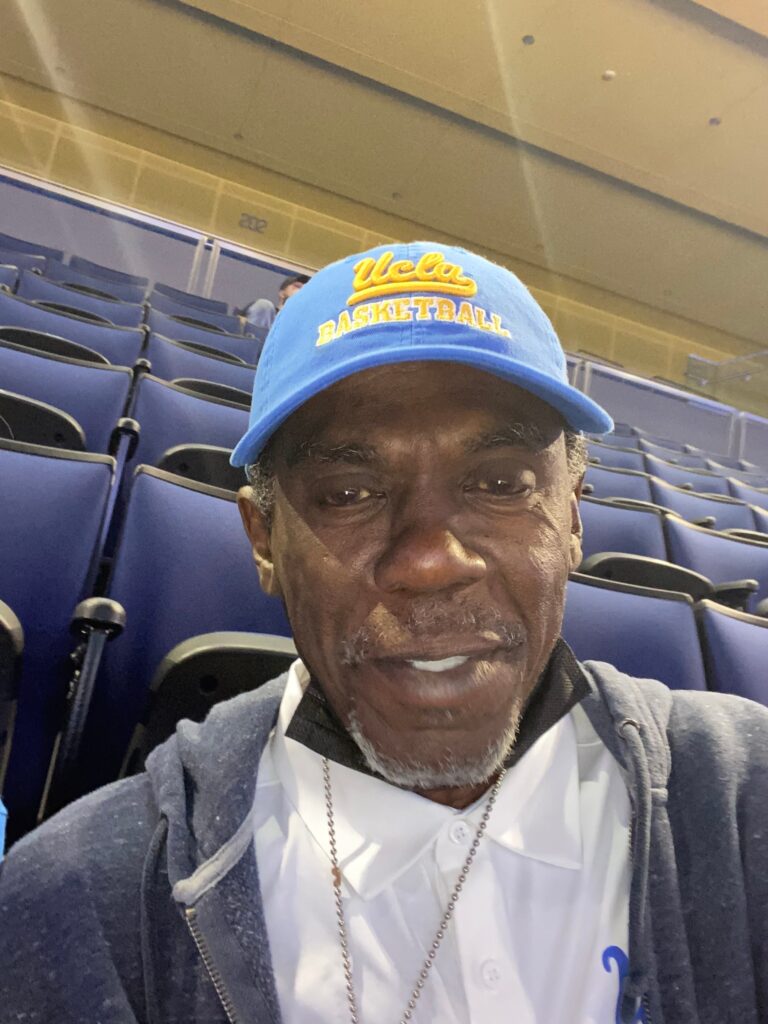

Tang at the UCLA game

Tang’s building in Longbeach, CA

The ocean front view

Tang (Wilbert) Watson was the highest scorer

Tang’s grandson Peyton plays basketball for UCLA

‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.”

Mark 12:31

Recent Comments