Lush fields spread out before us on both sides of the road as we drive from Somerset to Flowers Landing, a result of work done by modern machinery and chemical farming methods. It’s summer, and the crops that were planted in the spring are growing vigorously, promising a bounty in the fall. Road sides are overgrown with clover, Johnson grass, coffee weeds, and the occasional palmetto, thriving in the humid June weather, with little threat of being mowed. The river winds by our porch, its color resembling coffee with heavy cream, not as wide as in the spring, but higher than normal for this time of year. Rain peppers the surface of the muddy water and starts to drip off our eaves, giving a brief break from the smothering heat and humidity.

When it stops, the loud twitter of the wrens resume, hidden in the thick leaves of the sycamores, as do the far off calls of the doves. The occasional rap of woodpeckers echo through the woods, reminiscent of others long gone. Now home to the red-headed woodpecker, downy woodpecker, and the pileated woodpecker, among others, the refuge, and the once massive Singer tract, was the location where the great ivory billed woodpecker was last seen. That sighting drew national attention to the woods through which the Tensas River flowed, and the resulting research and documentation shed light on the environmental impact that mammoth companies like Chicago Mill were having. It also gives us a glimpse of the conditions that Jim and Etta Mae’s family, along with many others, were forced to tolerate.

Painting of ivory bill by Carl Bender

http://carlbrendersart.com/prints/wildlife-2/forest-carpenter-by-carl-brenders/

With a wing span of almost three feet, and a length of twenty inches or more, the ivory bill’s striking features included black feathers with patches of white, topped with a bright red crest on the male, and were awe-inspiring. Their call was unique, unlike other woodpeckers, and described as a kent sound. They earned their nickname from exclamations of “Lord, God!” when spotted in the wild by those lucky enough to see one. The pairs would mate for life and build their nests thirty to fifty feet high in dead snags, where they peeled back the bark to eat beetle larvae. Ivory bills preferred thick hardwood swamps with large amounts of dead and decaying trees and a pair required about 10 sq. miles of forest to feed themselves and their young, so they would have been sparsely populated even at their peak. (Wikipedia) As the large tracts of virgin timber across the southeastern United States disappeared due to logging, the ivory bill woodpecker lost much of its habitat.

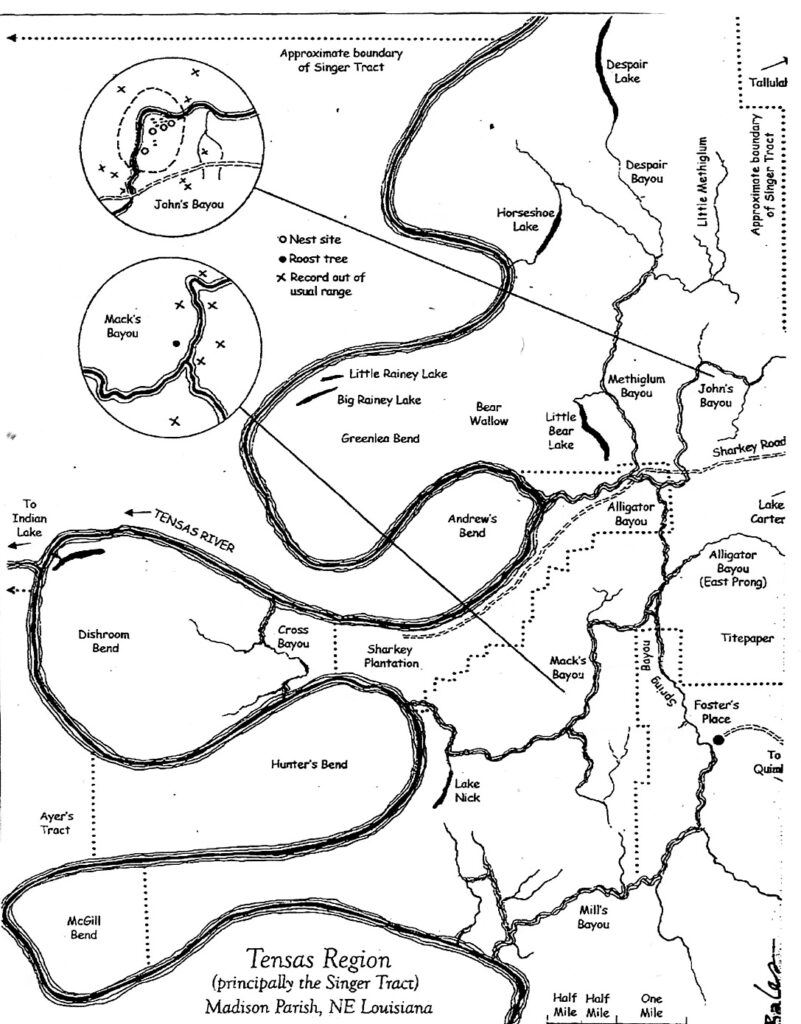

Considered virtually extinct by the 1920s, the scientific community took notice when a Louisiana politician from Tallulah, Mason Spencer, shot and killed an ivory bill on the Singer tract in Madison Parish in 1932, and bragged about it in New Orleans at a meeting of Louisiana wildlife officials who had given him a permit. Then, in 1934, Dr. George Lowery of LSU published Birds of Louisiana, giving publicity to the ivory bill find. This got the attention of Arthur Allen, founder of the Laboratory of Ornithology at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, who had spotted ivory bills in 1924 in Florida, a sighting which led to their death by hunters. He organized an expedition including himself, as well as, Cornell professor Peter Paul Kellogg, a graduate student, James Tanner, and a bird artist, George Miksch Sutton, to travel around the South using movie camera equipment to record rare bird sounds in the wild and search for more ivory bills. (Cornell.edu)(Singer.roots web)

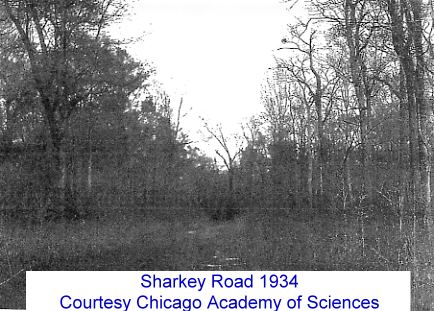

They traveled in two trucks, one loaded down with sound recording equipment and the other with camping gear, photo equipment, food and other supplies. In April 1935, right after Jim and Etta Mae had moved to Flowers Landing, the expedition arrived in Tallulah and stopped at Mason Spencer’s law office to question him about the bird he killed. They followed his hand drawn map to J.J. Kuhn’s cabin, a game warden for Singer, who was to be their guide. Traveling from Tallulah to Sharkey Road, which was not more than a set of ruts between towering trees, their heavy trucks struggled in the mud until they were rescued by Ike Page, and his son, sent by Kuhn to help them.

They left their trucks and put their camping gear in Ike’s wagon behind his team of mules, riding some five miles through the giant flooded timber to Kuhn’s cabin where they ate and slept, before hiking into the swamp to John’s Bayou the next morning, looking for the ivory bills. It took two more days of wading through palmetto, poison ivy, saw briars, and knee-deep water before the well dressed team of researchers, now rumpled and drenched with sweat, spotted an ivory bill nest with a pair of birds. (Philip Hoose, The Race to Save the Lord God Bird) “The whole experience was like a dream,” wrote George Sutton in his 1936 book Birds in the Wilderness. “There we sat in the wild swamp, miles and miles from any highway, with two ivory-billed woodpeckers so close to us that we could see their eyes, their long toes, even their slightly curved claws with our binoculars.”(Cornell.edu)

After the sighting, the team took the truck with its 1500 pounds of sound recording equipment to Tallulah for dry ground beside the city jail, dismantling it and rebuilding it in Ike’s wagon while some of the prisoners watched. Their equipment also included a fold down observation platform that could be “cranked up like a giant jack-in-the-box” to raise the observers to bird nest level.

Traveling all day with the wagon pulled by mules from Tallulah to reach the nest again, they spread a tent over the sound equipment. Using palmetto as a base for their sleeping bags to avoid the wet ground, they set up camp to observe and record the birds. Over the next two weeks, they were able to record the kent calls of the ivory bills, recordings which are still used today for authentication, and collect a multitude of photographs of the pair as they moved in and out of the nest. The team worked carefully, not wanting to disrupt the birds nesting, hoping to learn something about their behaviors that could lead to preventing their extinction.

James Tanner returned to the Singer tract in 1937 and spent three years studying the ivory bills and looking for them in other locations in the South, working on his doctoral dissertation which was funded by a grant from the Audubon Society. He discovered why they were decreasing, they were starving to death because there were no longer enough dead or dying trees for them to feed in, and the problem was about to get worse. Singer sold 6000 acres it held along the Tensas to Tendall Lumber Company in 1937, then sold the timber rights for the remaining acreage of the Singer Tract to Chicago Mill.

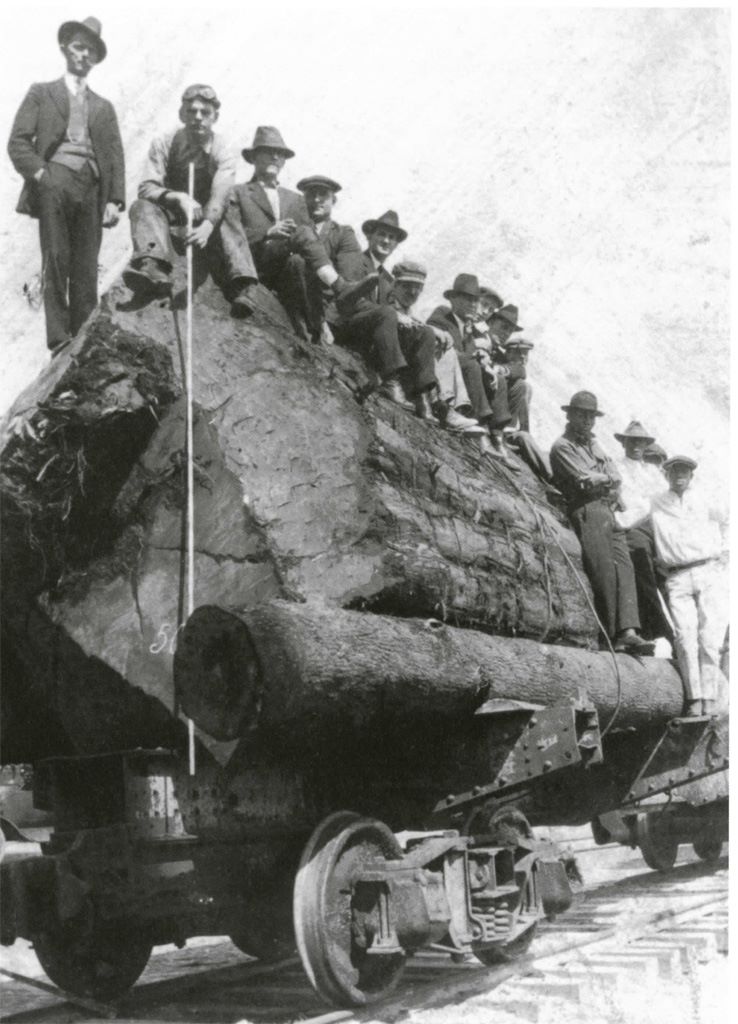

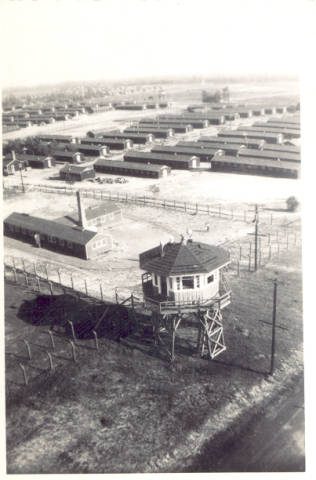

Chicago Mill Lumber Company cut top grade wood for furniture companies, including Singer for its sewing machine cabinets, and made wooden boxes of every kind and shape from the rest, including caskets, shell boxes and wagon seats. The company built sawmills near forests across the South and shipped the lumber down the Mississippi River on a fleet of company barges, feeding an appetite for wood that could not be satisfied. Chicago Mill began to cut trees in the Singer Tract at a rapid pace, building railroad tracks from Tallulah out into the woods and across the Tensas river at many locations, including the one that crossed at Flowers Landing. They set up logging camps with portable shacks brought in on the train for families to live in while loggers worked seven days a week “from can to can’t”, in rain and cold to cut the trees. When an area was cleared, the shacks were moved, and a new camp set up. (Philip Hoose, The Race to Save the Lord God Bird) Hermie Arnold recalls what he remembers about the logging camps, “We lived at the Chicago Mill camp on Sharkey Road in 1943-45. My dad, Gillis Arnold was an engineer on one of the engines that hauled logs off the Singer tract to the spur on the main line. Some of the families that lived at the camps were D.T. Sadler, S.C. (Red) Emfinger, Harmon Arnold, Morel Arnold, and a Singer family from Winnsboro. All the men had their wives and families with them at the camp. There was a bookkeeper, Mr. Foster from Tallulah, and a black man from Newellton who was a welder and all I knew him by was Uncle Top. I would see the German POWs. They were hauled in cattle trucks and guarded by armed soldiers.” It is estimated that at that time, 40% of the people living in the Tallulah area worked for Chicago Mill in some capacity.

In Hoose’s book he writes: The hoots of the barred owls, the electric chatter of the tree frogs, the hair-raising cries of wolves, and the tooting calls of the ivory billed woodpeckers were soon drowned out by the grinding, growling machines. “Those woods were loud,” recalled Gene Laird, who grew up in the forest during those years. “The train whistle was earsplitting—-four blasts meant ‘get off the track’. Axes rang, people yelled and whoop-whooped to be heard, and behind it all the crawler tractors hauling logs were always growling.”

The demand for wood increased with the onset of World War II, with the armed forces needing boxes to hold everything it shipped overseas, from airplanes to dry food. Chicago Mill had an increased market for its product, with no labor to build them, until it was supplied in an unusual way. German prisoners of war were shipped to New York, and then to communities in every state, including Ruston, Louisiana. Camp Ruston was one of the largest camps for German prisoners of war and supplied men for smaller satellite camps around the state, including Tallulah. The Tallulah fairgrounds was wrapped in barbed wire and turned into a POW camp, and the War Department allowed the prisoners to work on plantations and for companies like Chicago Mill. (64parishes.org)

Hoose’s book states: “The Germans were like a gift from heaven to Chicago Mill and Lumber Company. Now it could make money three ways in one project: it could clear the Singer Tract with workers who were practically free; it could sell as many boxes as it could make to the ravenous War Department; and it could sell the cutover land to rural families who wanted cheap farmland. Chicago Mill didn’t even have to clean up the mess it had made. ” The waste, you wouldn’t believe it,” recalled Gene Laird. “If you stood at a cut-down tree and it didn’t measure three feet around, they’d just leave it on the ground. “

Valiant efforts to persuade Chicago Mill to stop cutting on the Singer tract, or at least the area where the ivory bills lived, failed. Led by the Audubon Society, the governors of Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi, and Louisiana, as well as, officials of the Roosevelt Administration joined in the fight. On December 8, 1943, John Baker of the Audubon Society reported the results of a meeting in Chicago Mill’s downtown Chicago boardroom like this: “Chicago Mill refused to cooperate in any way, and said that it would not enter into any deal unless forced to. The Chairman said, among other things, ‘We are just money grubbers. We are not concerned, as you folks, with ethical considerations.’ They would not help in any way with the creation of a park or refuge unless forced to do so.” (Phillip Hoose: The Race to Save the Lord God Bird)

News of the ivory bill find on the Singer tract appeared in newspapers across the country, and scientists, students, photographers, artists and curious sight seers continued to visit the Singer woods on and off as late as 1944, until the last of the birds disappeared. My brother, Kenneth, remembers Grandpa Willhite (Jim) telling him about the Cornell University expedition and their equipment in the woods, likely seen on their frog hunts to Mack’s Bayou, Alligator Bayou, or Methiglum Bayou which were near the area of the expedition. Derwood was reported to have helped guide some expeditions, since the game warden, J.J. Kuhn had been forced to resign when he defied powerful politicians who wanted him to allow their cronies to hunt freely on the Singer Tract with no consequences. (The Race to Save the Lord God Bird)

The damage inflicted on the primeval hardwood forest of the Singer Tract was a painful part of the Willhite family’s daily lives at the time, with a Chicago Mill train track running near their house at Flowers Landing. Jim was able to buy some of the cutover land for farming, and they continued to hunt, fish and trap along the Tensas, steering clear of areas that were being heavily cut.

“Is it not enough for you to feed on the good pasture? Must you also trample the rest of your pasture with your feet? Is it not enough for you to drink clear water? Must you also muddy the rest with your feet?”

Ezekiel 34: 17-18

Interesting and well written

Again very interesting reading about some things that I was never aware of. ! Looking forward to Chapter 11👌

My father, Horace Muse, whose family lived on Tensas River in the Tensas Bluff area, went to work at 16 years of age, for a lumber company hauling logs from across Tensas River. He was so young that his parents had to sign a document stating that he was their son, and giving their permission. They rode the trains up into the woods and stayed there in a camp all week. He said that mud was about six inches deep on the floor where they lived. The train would take the workers into Tallulah on Saturday nights if you wanted to go.

My Uncle Brodia Muse said he worked some of these German prisoners from the camp at Tallulah on the farm during the war. He stated, “they were just blond, blue-eyed, boys like the rest of us. They were very nice and polite.”

How I wish my father were here to read these blogs. He would enjoy them so much.

I have heard my neighbor’s talk about Sharkey Road and their life growing up their. Sadly Mrs. Hazel has died , but her husband is still alive and still has a good mind . I will tell his daughter to let him see this. Very good writing.